Squaring And Levelling Britain’s Symbolic Kerbstones

Written by Ashley Cowie. First published 01 November 2016 - republished 22 March 2024.

Abstract: This research investigates over 6,400 kilometers (4,000 miles) of British urban areas, analyzing geographic coordinates derived from approximately 3,000 photographs of symbolically inscribed kerbstones. The study reveals a distinct pattern within Glasgow’s urban landscape, offering a novel perspective on Victorian-era Masonic practices through this unique geographical lens.

Keywords: British urban environments, Kerbstones, Symbols, GPS values, Freemasonry, Plague victims, Wartime utilities, Cartographic positioning, Victorian-era, Stone-masonic traditions.

Introduction: Delineating Britain’s Symbolic Kerbstones

Embedded within British urban infrastructure are cryptic inscriptions, intricate symbols etched upon kerbstones, that form a concealed network of interconnected Victorian-Era stonemasonic symbolism. The symbols, dating back over a century, present a labyrinth of messages concealed from the casual observer, but this research presents a solution to one aspect of this profound architectural communication.

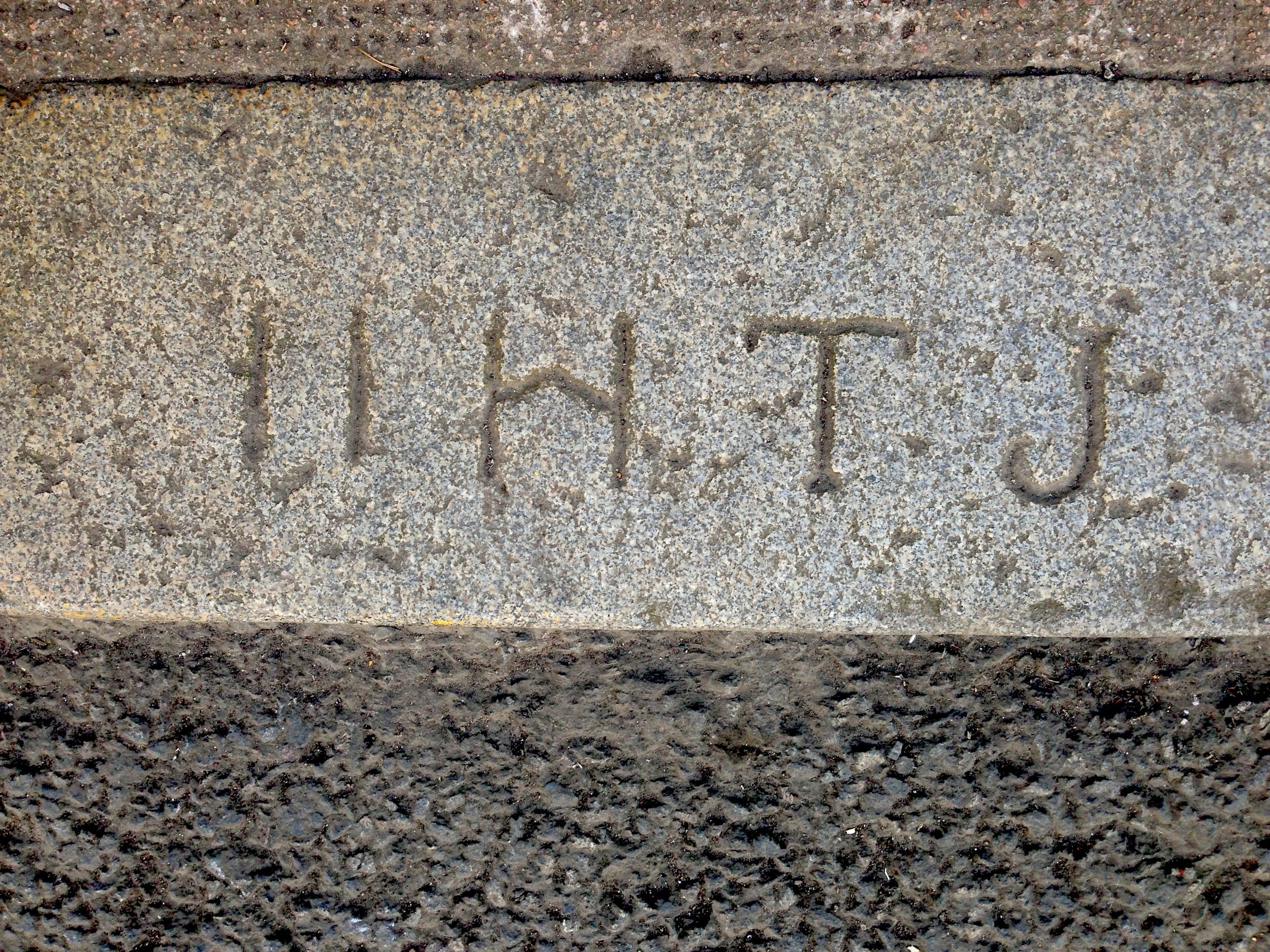

Figure 02. Demonstrating a fusion of symbols and initials, this kerb stone is located on the lower east side of Queen’s Park, in Shawlands, on the south side of Glasgow.

The motifs and inscriptions under examination, which include letters, points within circles, equilateral triangles, squares, stylized crosses, and different types of arrows, collectively constitute a theater of visual cues, prompting a critical exploration of their potential stonemasonic origins. Moreover, the inclusion of inscribed letters bearing antiquated fonts and serifs, augments this hidden narrative, bespeaking an age-old code that has thus far escaped discernment.

This investigation provides an overview of the context and historical backdrop surrounding the covert symbolism entrenched within British street architecture, looking at both the geometric and typographic attributes, bringing together cartography with stonemasonic traditions to provide a potential solution to one aspect of this enigma.

The pivotal breakthrough in unraveling one aspect of this national mystery stemmed from an intense personal dedication, bordering on an unyielding obsession. Between 2008 and 2012, armed with a DSLR camera and a lightweight tripod, an extensive exploration of the streets in Glasgow and London ensued, encompassing a distance of around 6,400 kilometers [4,000 miles].

My primary objective was to compile a comprehensive photographic database featuring kerbstones adorned with cryptic symbols, including the location coordinates of each one, and this extensive corpus currently comprises approximately 3,000 documented instances. Subsequently, the expertise of Glaswegian computer coder Alex Laing was enlisted to devise an algorithm, to facilitate a visual representation of the amassed dataset on mapping software.

The earliest visualizations of these seemingly disparate GPS coordinates, upon the cartographic canvases of Glasgow and London, constituted the primary step towards identifying a pattern within the seemingly chaotic array of kerbstone symbols.

Figure 03. First map rendering of a section of Kensington and Earls Court in London, displaying the locations of individual inscribed kerbstones bearing the carved letter ‘H’.

Debunking the benchmark hypothesis

The term "matrix," as construed outside geological contexts, denotes a "cultural, social, or political environment in which something develops." [1] A frequent misstep observed among researchers engaging with kerbstone symbols lies in their proclivity to draw unwarranted parallels between these symbols, particularly arrows and triangles, and the triangular configuration of Ordnance Survey benchmarks. The latter, numbering 35,000 and etched by Victorian masons across the expanse of the UK, facilitated cartographers using theodolites to measure altitudes above sea level. [2]

The 'benchmark hypothesis' crumbles upon considering that permanence was an indispensable criterion in the selection of potential sites. Therefore, ordnance benchmarks were generally etched into stationary vertical structures like bridges, cornerstones of civic edifices, church walls, and the pedestals of statues and monuments, and not on volatile kerbstones inherently subject to vibrations induced by horse-drawn carts and susceptible to substantial displacements during inclement weather conditions.

Figure 04. OS benchmark carved on a vertical wall at Morville school, Bridgnorth, Shropshire, England. CC 3.1.

The problematic plauge memorials theory

Soho Square in London features no less than 60 inscribed kerbstones bearing triangles, groups of letters, and 47 Greek and Maltese crosses. In 2009, these kerbstones became the passion of New York artist, Lauren Drescher, who in the January 30 edition of “West End Extra” said “Ask Jeeves doesn’t have a clue, archaeologists at the British Museum are stroking their chins; university historians have drawn a complete blank, and Indiana Jones is unavailable”. [3]

Following thorough contemplation, artist Lauren Drescher presented her reflections to historians associated with The Soho Society, the British Museum, the Museum of London, Westminster Archives, and the hierarchy of the Worshipful Society of Freemasons. Drescher's audacious engagement with London Freemasons was underscored by her assertion that, while the engraved symbols bore semblance to stonemasons' marks, “such an interpretation lacked cogency.”

Figure 05. One of the 47 cross-marked kerbstones in London’s Soho Square.

Drescher contended that the carved motifs exhibited “an unduly simplistic design, contrary to the typically intricate nature of stonemasons' marks.” By disqualifying the possibility of stonemasons' involvement, the artist proposed an alternative thesis concerning the 47 Soho Square crosses, suggesting they were “miniature grave markers commemorating the extensive loss of life during the Great Plague of London,” which occurred from 1665 CE to 1666 CE.

The foundation of Drescher's theory rested upon the premise that families bereaved by the plague, confined to the vicinity due to quarantine measures, may have “offered coins to local street urchins, beseeching them to memorialize their departed loved ones.” Intrigued, “West End Extra” conducted inquiries with the British Museum and the Museum of London, and both institutions “expressed keen interest” in Drescher's somewhat morbid conclusion.

However, upon retrospective analysis, it becomes apparent that this theory attributing the kerbstone carvings to victims of the plague is an imaginative and speculative construct. Regrettably, Drescher’s conclusion was based on an extremely limited subset, in this case, merely 47 selected examples from a dataset comprising thousands within the analytical framework. Furthermore, the theory fails to account for the thousands of crosses carved on kerbstones in parts of Britain that were unaffected by the plague, that affected London.

Negating service and utility marks

In 2013, Peter Dolan, a scholar affiliated with the Geological Society of London published a paper titled “Kerbstone conundrum,” in which he sought to proffer insights into the nature of the kerbstone inscriptions, followed by a second paper in 2016 titled “Kerbstone Markings 2”. [4/5]

In the first paper, the author initially envisions Victorian quarrymen imbuing stones with symbols of work pride, however, as analysis progresses, three main interpretations emerge: “Pedigree” (quarry marks), “Supply Chain” (distribution or production marks), and Local Information (indicating nearby services). The author critically assesses each group but remains puzzled by several aspects, including the absence of kerbstone marks in affluent areas, which suggests the marks were executed on the streets. Ultimately, the author concluded that “the true meaning of these symbols remains elusive, leaving the conundrum unresolved,” but his observation of an “absence of kerbstone marks in affluent areas” directly supports, and is supported by, the solution presented herein.

Figure 06. Author examining a symbolic kerbstone inscription on University Avenue, in Glasgow’s westend.

In his first paper, Peter Dolan initially explores the idea of Victorian quarrymen imbuing stones with symbols representing their pride in their work. However, as the analysis progresses, three main interpretations of these symbols emerge: "Pedigree" (related to quarry marks), "Supply Chain" (associated with distribution or production marks), and "Local Information" (indicating nearby services). The author critically evaluates each interpretation and encounters paradoxes, such as the lack of kerbstone marks in affluent areas, suggesting that the marks were made on the streets, which directly aligns with the solution presented in this paper. [4]

In his second paper, Dolan refers to this mystery as "an enigmatic historical conundrum," and employing a principled approach, he readdresses his first list of potential answers, defining four new groups: parish boundaries, borough maintenance boundaries, government property markings, and service marks (specifically electrical, gas, telephone, and water-related symbols). [5]

Regarding governmental property, particularly the arrow markings in Whitehall, Dolan underscores “the lack of exhaustive research,” cautioning against “premature conclusions about their meaning.” In the context of service marks (electrical), Dolan noted “a lack of uniformity and supporting historical evidence. However, acknowledging the importance of solving the mystery, Dolan pointed to the need for comprehensive research and archival investigation to decode the symbol’s meanings accurately.

Figure 07. Situated on a street corner on University Avenue in Glasgow, this arrow most probably represents a delineation mark.

In his second paper, Dolan refers to this mystery as "an enigmatic historical conundrum," and employing a principled approach, he readdresses his first list of potential answers, defining four new groups: parish boundaries, borough maintenance boundaries, government property markings, and service marks (specifically electrical, gas, telephone, and water-related symbols). [5]

Regarding governmental property, particularly the arrow markings in Whitehall, Dolan underscores “the lack of exhaustive research,” cautioning against “premature conclusions about their meaning.” In the context of service marks (electrical), Dolan noted “a lack of uniformity and supporting historical evidence. However, acknowledging the importance of solving the mystery, Dolan pointed to the need for comprehensive research and archival investigation to decode the symbol’s meanings accurately.

The complexities of stonemasons signatures

In 1598 CE, William Schaw, the Master of Works to James VI of Scotland for castle and palace construction, enacted regulations and ethical guidelines for stonemasons. These directives stipulated that upon their induction into the Stonemasons' guild, "every mason was obligated to register both his name and his distinct mark." [6] The integration of stonemasons' marks served not only to discern individual contributions for precise remuneration, given that stonemasons were compensated based on the quantity of blocks laid, but also to ensure quality workmanship through traceability. [7]

Presently, within Freemasonry, this mediaeval tradition endures through the initiation of the Mark Master Mason degree, wherein Freemasons craft their own unique Mark as an identifier, thus perpetuating the legacy of their symbolic predecessors. In the medieval period, only the most adept and privileged stonemasons were engaged in the construction of religious and civic edifices. and the majority of historical stone workers were quarrymen extracting massive sections of rock from hazardous cliff faces. [8]

According to the “Old Jobs” website, during the Victorian era, the production of kerbstones involved distinct labor roles, initially executed by 'lumper uppers' and 'cutters' who prepared the blocks to approximately 70 percent of the final ashlars. Subsequently, teams of 'scelpers' refined these rough blocks into rectangles, achieving an accuracy of about 95%. Finally, 'dressers,' with skilled precision, levelled the new ashlar to less than 0.5 degrees of accuracy, rendering them ready for conveyance to the construction sites. [9]

Considering this sequential process spanning from quarrying to the construction site, one might assume that many of the kerbstone marks were etched during the production stages at quarries, but this would be erroneous. In his first paper, researcher Peter Dolan explored the idea that kerbstones held the imprints of quarry merchants and transport companies responsible for the storage and transportation of the blocks to new locations across Britain. However, the author pointed out that in many cases, “no marks were found on kerbstones in more affluent streets.”

Furthermore, Dolan noted that often “two ∆s were widely spaced on the same kerbstone,” effectively negating the idea that the stones were inscribed by masons at quarries to mark their work. In support of these arguments, in Saltaire, kerbstones carry numerous marks which Dolan said “would seem to be totally unnecessary for delivery since they were sourced locally for nearby use by a single customer.” [10] All observations point towards the stones having been inscribed after their delivery, on the streets of Britain.

Figure 09. Lumper uppers chaining a 15 ton lump of rock before swinging it onto a trailer.

Figure 10. Victorian scelper chipping a stone into form.

Identifying a pattern within Glasgow’s inscribed kerbstones

With each proposed theory subject to argument and often rebuttal, this strongly implies a lack of a singular systematic or underlying pattern. Instead, it is conceivable that these markings represent fragmented elements from the contested theories outlined earlier. Nevertheless, amidst the apparent complexity, an intriguing pattern was identified in Glasgow, indicating the potential involvement of the stonemasons responsible for the placement of the stones on the streets, supporting the findings of Peter Dolan.

Analyzing approximately 3,000 geographically tagged photographs, with approximately 2,000 instances within Glasgow, clusters of symbolic inscriptions emerged. Subsequently, an investigation was conducted throughout June 2014, documenting clusters of kerbstone symbols within Shawlands, on the south side of Glasgow, spanning a one-kilometer square zone extending west from Kilmarnock Road.

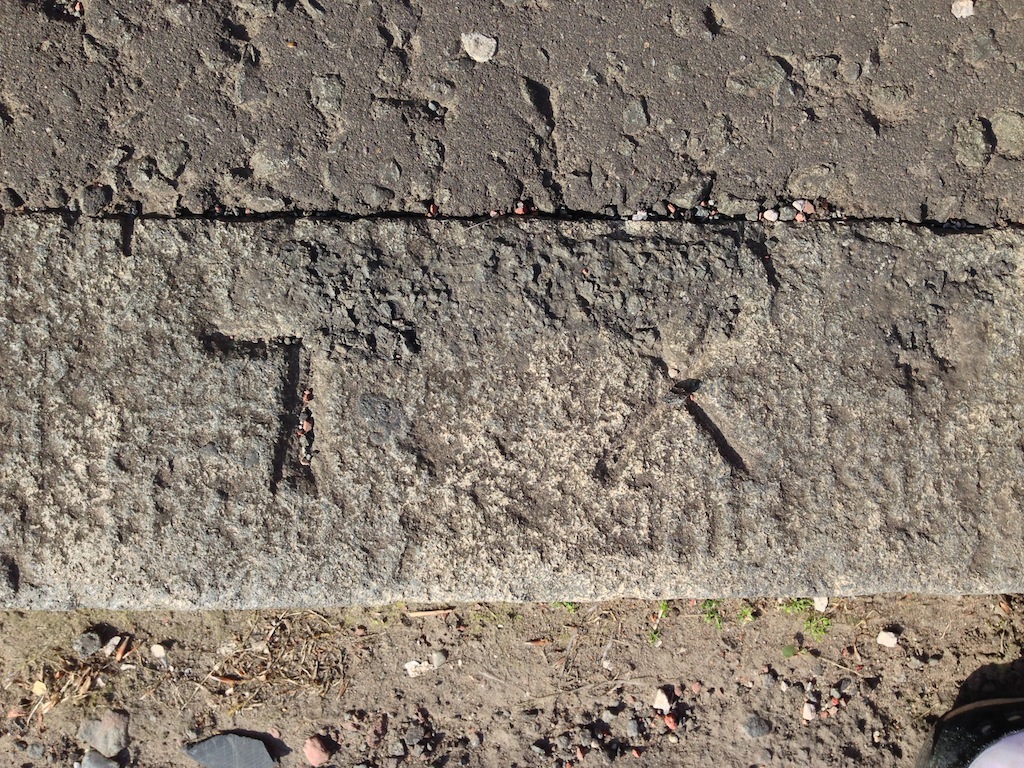

A total of 306 individual stones were cataloged, revealing an abundance of triangles, crosses, and arrows, and on certain streets clusters of initials were identified, predominantly: J, H, and T. Additionally, numerous pairs and triplets of initials were identified, including J.Z., J.A., J.P., J.H., H.T., P.J., E.V., H.T.J. and E.H.V., along side ornate four letter combinations such as H.T.J.T..

Figure 11. This letter ‘T’ is located the on the south side of Queen’s Park, and represents the most common letter found on Glasgow’s symbolic kerbstones.

Research focused on a specific cluster, or strip, of five kerbstones bearing the initials J.H., located on the north pavement of Holmbank Avenue, adjacent to Kilmarnock Road in Shawlands. Proceeding southward along the north pavement of this Victorian thoroughfare, the initials J.H. were carved on every 11th kerbstone, with no markings on the intervening stones. It was posited that the likelihood of quarry-marked stones being unloaded from pallets in such a structured configuration was exceedingly low. A plausible alternative was that J.H. held a position of authority over a team of stonemasons, and that the initials potentially denoted a day’s work laying kerbstones on the street.

Figure 12. This ornate 'H.T.J.T.' configuration appears in Regent Park Square in Strathbungo, Glasgow.

Compensation for stonemason teams was typically contingent on the number of stones laid per designated time frame, whether daily or weekly. Consequently, a site foreman on Holmbank Avenue could conveniently ascertain the mason's remuneration by merely traversing the street at week's end and tabulating the instances of the J.H. marked stones. It can be speculated that instances where kerbstones were inscribed with two or three individual sets of initials, such as H and J.H. culminating in J.H.T., point towards collaborative efforts between two individual masons, or gangs thereof.

Figure 13. Red dots indicate kerbstones inscribed with the letters J.H., which appear every 13 to 14 stones in Holmbank Avenue, off Kilmarnock Road, Glasgow.

Conclusions

This investigation has unearthed the fragments of a pattern from within the seemingly disordered arrangement of inscribed kerbstone symbols, strewn across British urban landscapes. While the symbols represent a fusion of timeworn signatures chipped by quarrymen, transport, and storage companies, mixed with delineation, utility, and service marks, there exists a propensity of initialed stones defining groupings of around 11 stones, perhaps indicating the number of stones set in a street by a gang of stonemasons in one day.

These findings offer a simple structured logic, and this newfound comprehension is expected to pave the way for future researchers to delve deeper into specific aspects of the street builders craft, including their efficiency, collaboration dynamics, and the nature of building projects they undertook.

Moreover, the ongoing enrichment of the extensive database of symbolic UK kerbstone symbols is actively facilitated by public involvement as we encourage individuals to contribute to this evolving research by submitting photographs of similar stones along with embedded GPS data through the "Contact" page in the main menu. This collaborative effort will undoubtedly enhance our understanding of the intricate connections between these symbols and the masonic traditions, further illuminating lost aspects of British architectural history.

References

“Matrix”. Cambridge Dictionary. Link

Ordinance Survey. The complete benchmark archive. zipped CSV (12 Mb). Link.

Wellam, J. (30 Jan 2009). Crosses in the square mystify the experts. West End Extra. Link.

Dolan, Peter (2013). Kerbstone Conundrum. Geological Society of London. Link

Dolan, Peter (2014). Kerbstone Markings 2. Geological Society of London. Link

Alexander, J, S. (2007). The introduction and use of masons' marks in Romanesque buildings in England. Mediaeval Archaeology. 51: Pg 63–81.

Grand Master's Royal Ark Council. (2010). Royal Ark Mariner Ritual No.1 London: Grand Lodge of Mark Master Masons

Brooks, Frederick William. (1952). Masons' Marks. East Yorkshire Local History Series. Vol. 1. York: East Yorkshire History Society.

Dictionary of Old Occupations. A-Z Index. Link

Dolan, Peter. (2013). Kerbstone Conundrum. Geological Society of London. Link

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6872-4759

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6872-4759